Millennial cranial surgery

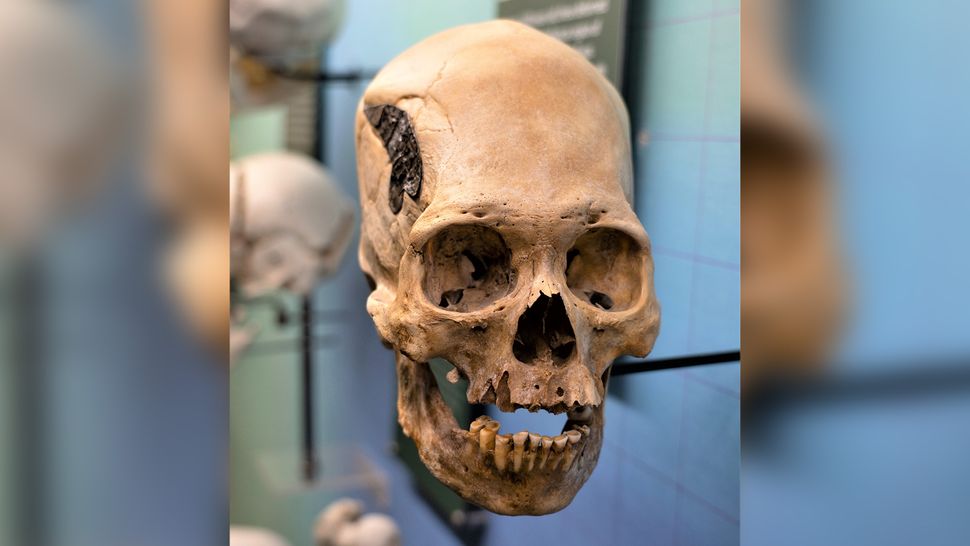

The skull is believed to have belonged to a warrior wounded in the head during a battle. The metal implant would have been inserted during a surgical procedure to treat the wound. According to museum representatives, the patient survived the surgery. “Based on the broken bone around the repair, you can see that it is well fused. The surgery was successful,” they said.

Elongated skull with metal implant

In addition to this potential implant, the skull has a hole under the metal, possibly created through a surgical procedure known as trepanation. This technique has been used by different peoples of the world for thousands of years to treat cases of head trauma, headaches, epileptic seizures and mental illness. Previous studies already pointed out that the Incas applied this treatment.

Elongated skull with metal implant

But not everyone is convinced of the authenticity of the piece. John Verano, professor of anthropology at Tulane University in the United States, told Live Science that the skull may have been forged. He hypothesized that the metal implant may have been placed later to enhance the piece. Kent Johnson, a professor of anthropology at SUNY Cortland University in New York, said the metal implant could be authentic, but that more detailed analysis would be needed to prove the theory.

The fact that the skull is elongated also has an explanation . For thousands of years, human groups from around the world have intentionally modified skulls by tying babies’ heads with cloth or trapping their heads between two pieces of wood. Researchers believe that generally the practice represented belonging to an ethnic or social group. This strengthened the sense of collectivity and community among the group.

This skull from Peru has a metal implant. If it is authentic then it would be a potentially unique find from the ancient Andes. (Image credit: Photo courtesy Museum of Osteology)

The way that the skull, which was given to the Museum of Osteology in Oklahoma City, has a cone shape is not really strange, as Peruvians during old times were known to crush kids’ heads with groups during advancement to accomplish the unmistakable shape.

Notwithstanding, the metal embed in this skull is profoundly uncommon and, if bona fide, would possibly be an extraordinary find from the old Andean world.

The Museum of Osteology, which has posted a few photos of this skull on its Facebook page, said its specialists can’t check the credibility of the metal embed right now. An exhibition hall agent let Live Science know that no scientifically measuring has been done and a classicist presently can’t seem to inspect it very close.

Tests should be led to decide whether the metal embed is genuine researchers told Live Science.

Credits : museum of osteology

Tests should be led to decide whether the metal embed is genuine researchers told Live Science. (Picture credit: Photo kindness Museum of Osteology)

Is the embed valid?

Live Science conversed with a few researchers not subsidiary with the historical center to get their interpretation of the embed’s genuineness, and in general their perspective was blended. Some were incredulous and recommended the embed is an imitation, while others suspect the embed could be the genuine article. In any case, a few logical tests should be done before a last assurance can be made regarding whether the embed is legitimate, the researchers said.

“I’m very questionable that this is anything true,” John Verano, a human studies teacher at Tulane University in Louisiana, told Live Science in an email, alluding to the metal embed perhaps being a current imitation regardless of whether the skull is genuine. “In a couple of words, I think this is a manufactured thing to make the skull a more significant collectible,” Verano said. This metal embed might have been embedded ages ago, before either the gallery or the benefactor claimed it.

Verano has analyzed a few Andean skulls that purportedly have metal embeds and distributed a paper on the theme in 2010 in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. In the paper, Verano portrays skulls that apparently held metal inserts, however they were either falsifications, or the metal was not a careful embed the slightest bit but rather was utilized as a grave contribution.

Credits: museum of ostology

Different researchers let Live Science know that it’s conceivable the metal embed could be genuine, yet it’s too soon to say for sure until additional tests have been completed. “I’ve never seen anything like this. In view of the photos, it appears as though the metal piece was meagerly pounded into shape,” Danielle Kurin, a humanities teacher at University of California, Santa Barbara, told Live Science in an email.

“In view of the crack examples, this individual – [who] seems to be a more established male – experienced a huge obtuse power injury to the right half of the head. The way that the transmitting and concentric crack lines give indications of mending proposes this individual made due at minimum a little while to months,” Kurin added.

Since metallurgical innovation shifted across the Andes at that point, tests on the metal in the skull could assist with revealing insight into where it was made, Kurin said. “It would likewise be useful to have the skull X-rayed to decide whether the piece of metal is covering a trepanation opening as well as an open cranial crack.”

There are a couple of cases from past disclosures where, after a trepanation, a piece of the individual’s bone or a gourd was put in the opening that was removed, Kurin said. Also, in a 2013 American Journal of Physical Anthropology article, Kurin gave an account of a situation where an individual who resided in Peru around 800 quite a while back wore a tight-fitting skull cap that had a metal cap sewed onto it. They wore the cap like a head protector, giving security to the area cut out by trepanation.

Kent Johnson, a humanities teacher at SUNY Cortland, likewise said that the metal embed could be bona fide yet again said that tests should be finished. In any case, whether or not or not the embed is genuine, the individual it was put on endure a horrendous physical issue.

“Depicting this person as a survivor is fair. There is broad injury to the right half of the skull influencing the front facing, transient and right parietal bones,” Johnson told Live Science in an email, taking note of that the individual appears to have made due for a period after these wounds. “There is proof of recuperating where the edges of the cracked bones had adequate opportunity to bounce back together.”

It’s not satisfactory right when tests on the skull will occur.